- Home

- Jesse Taylor Croft

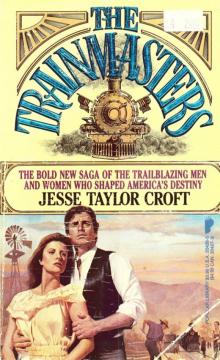

The Trainmasters

The Trainmasters Read online

A Special of American Pioneers

The Barmen and Women Who

Seized the Future

and Rode It to Success

JOHN CARLYSLE—Born to be a railroad man, this brawny and brilliant engineer led his steel-driving men across a wild country… to follow his heart into a tumultuous era of deadly rivalries and blazing desires.

•

TERESA O’RAHILLY—An Irish immigrant and stunning beauty, she would be forced by fate to leave the servant class to become the pampered courtesan of wealthy men. Then one young gentleman dared to woo her and—if it was not too late—make her his own.

•

KITTY LANCASTER—The vivacious daughter of a railroad magnate, she would be filled with Yankee fire and determination… and ready to challenge desperate men and hardship to win the man she loved.

•

DANIEL DREW—A robber baron of the Gilded Age, money was his god. A genius with a stock certificate and a balance sheet, he financed and manipulated his way to the top. Yet he was never a man to resort to violence… he hired others to do it for him.

•

GRAHAM CARLYSLE—John Carlysle’s son, a young man raised with the hammering of work crews echoing in his blood, he had dreams of a glorious future in his heart… and terrible struggle in his future.

Copyright

POPULAR LIBRARY EDITION

Copyright © 1988 by Warner Books, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Popular Library® and the fanciful P design are registered trademarks of Warner Books, Inc.

Popular Library books are published by

Warner Books, Inc.

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com.

First eBook Edition: September 2009

ISBN: 978-0-446-56703-9

Contents

Copyright

Part I

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Part II

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

The Colorado Trilogy from DOROTHY GARLOCK …

Part I

One

April 1852

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Mrs. Charles Lancaster was more than thrilled. She was exhilarated. In fact, her enthusiasm was so great she felt that the top of her head might fly off.

She was about to christen a brand new, very beautiful, very powerful locomotive in front of Philadelphia’s most distinguished citizens. It was perhaps the most exciting event she had attended in months. As the train moved slowly toward her, Kitty Lancaster felt her heart beat more rapidly. Her hands, gloved in exquisite white lace, clasped and unclasped in front of her.

Such emotion regarding a locomotive was unusual for a woman in 1852, but Kitty Lancaster was more than just a little interested in the power of iron and steam and speed; she was fascinated by it.

As the locomotive drew nearer, Kitty turned to the man standing next to her on the reviewing platform. “Mr. Baldwin,” she said, “it’s lovely, truly lovely.” And then, taking his hands in her own, she added, “I congratulate you.” Her awe was quite evident.

The locomotive builder bent his head toward her and smiled. “I thank you, Mrs. Lancaster, for your glowing opinion of my new machine. And I’m delighted that you will be the one to christen it. I pray that it will continue to perform as beautifully as it appears in your eyes.”

The bright and gleaming new locomotive had recently been completed in Mr. Baldwin’s Philadelphia shops. Trailed by four equally new, equally shining passenger cars, it pulled slowly to a stop in front of the reviewing platform where Mrs. Lancaster, Mr. Baldwin, and a large number of other greater and lesser dignitaries stood. Huge gouts of steam erupted from the engine, and there was a great grinding scream of metal on metal, followed by the clank and clatter of cars banging against their couplings. And in a few moments the train came to a halt only five feet from the front of the stand.

The reviewing platform had been set up at the intersection of Broad and Market streets; the train had drawn up to the platform on the Market Street tracks. A refreshment tent was placed beside the platform,’ and another, larger tent was set up opposite it to accommodate the dignitaries should the weather change drastically. But it was a splendid, warm April Saturday with no sign of a cloud.

Flanking the track was a large, noisy crowd; the throng spilled out into the vacant lots on either side of Market Street. Everyone seemed to be enjoying themselves, cheering and clapping whenever the mood struck. In front of the refreshment tent, a brass band had begun to play when the train stopped. The lively march had been composed for the occasion by Will Stewart, a member of the faculty of the University of Pennsylvania Conservatory of Music.

The locomotive was indeed a wonder, perhaps the finest piece of equipment produced by the finest shop in America. It was, first of all, massive, weighing nearly sixty thousand pounds, and it was powerful; it could easily pull the load now attached to it up the steepest mountain grade. And it was splendidly decorated. The stack, the firebox, and most of the steam dome were typically painted black, but the rest of the engine nearly exhausted the spectrum. The boiler was robin’s-egg blue; the wheels and the pilot—what many came to call the cowcatcher—were vermillion red. The outside of the cab was made of polished teak, covered with elaborate scrollwork in gold. Underneath the window was a realistic painting of a Bengal tiger stalking unseen prey in an emerald-green jungle. The locomotive’s nameplate, which was set well forward on the boiler, was in great, ornate brass letters: TIGER. Another jungle painting appeared on the side of the headlight. And American flags flew from bronze stanchions on top of the pilot.

The locomotive’s tender was painted a delicate rose, with the railroad’s name—PENNSYLVANIA RAIL ROAD—inscribed on a flowing blue ribbon and surrounded by curlicues of gold.

“You are a truly glorious machine,” Mrs. Lancaster said under her breath.

“Excuse me?” Matthias Baldwin asked, not quite hearing her.

She laughed a most engaging and vivacious laugh. “Oh, I hope you didn’t think I was addressing you, Mr. Baldwin,” she said, grasping his hands again. “I was thinking about your glorious engine.”

Matthias Baldwin smiled and raised his eyebrows.

“May I tell you a secret?” she asked.

“Of course. Please do.”

“I won’t shock you?”

“I doubt that,” he said and smiled.

“I want to drive that machine,” she said. “I want the steam to push up until the boiler’s near to bursting. I’d like to hurdle down the track faster than any human has ever traveled, with the wind blasting my face, my hair streaming behind me. God! What I would give to do that!” She looked at him. “Are you still not shocked?”

He laughed. “No. Not shocked. Though I have to admit that you are a most unusual and enthusiastic young woman,” said Matthias Baldwin, liking her and admiring her exuberance. “Which is matched only by your great beauty.”

“I am enthusiastic for railroads, Mr. Baldwin,” she said, rushing by the compliment as if she had not heard it. “Nothing so excites me as they do.”

John Carlysle, an Englishman who had arrived in Philadelphia from London only two weeks before, was not among those invited to the reviewi

ng stand. But he had stationed himself and his three sons as close as possible to it. Because he wanted them to have the best view of the proceedings, he had found space next to the front of the locomotive, just to the side of the pilot.

From there he could see practically without obstruction the stunning young woman in green silk talking animatedly with Matthias Baldwin, the locomotive manufacturer. He reckoned that she was in her late twenties or early thirties. She was tall and quite slender, and her hair was very nearly as black as Tiger’s smokestack.

“She is quite a beauty, Father, isn’t she?” Graham Car-lysle said, noticing where his father’s attention was directed.

Graham was twenty years old, and his father’s age was a year short of double that. In spite of his young years, Graham had already spent considerable time in the company of a number of more than ordinarily beautiful members of the opposite sex, many of whom were more than a little older than he was. His success with the ladies, and his seeming indifference to any kind of permanent relationship to any one of them, often bothered—and even angered—his father, who steadfastly believed in the Bible’s teachings regarding one man cleaving to one woman.

Still, he couldn’t quarrel with Graham’s assessment of the lady in front of them. “She’s the only beautiful thing on the platform,” he said.

“I wonder who she is,” Graham said.

“Shall I tell you?” John Carlysle asked, smiling, pleased that he knew more than his son about this one woman, at least.

“Yes, tell me who she is,” Graham said.

“Her name is Kitty Lancaster,” John said.

“Have you met her?” Graham asked.

“Not yet, but I expect I will. I expect I’ll be meeting most of the people on that platform soon. Many of them control the Pennsylvania Railroad.” John Carlysle was due shortly to take up a new position with the railroad.

“And she is a power at the railroad?” Graham asked, surprised that a woman might have a position here that only men might take in England. He was new to America, however, and he was aware that it was a nation full of shocking novelties. So he was prepared for very nearly any American outrage.

“Yes, indirectly,” John said. And then, noticing the confusion on Graham’s face, he added, “Actually, she has considerable influence but no outright power.”

“Well, is she rich?” Graham asked with a grin. “And,” the grin vanished, “is she married? Is she then hopeless for me?”

“I’m sure she’s wealthy,” John said. “But I’m afraid she’s been married, lad, though Mr. Lancaster is no longer with us. He was killed in the recent war with Mexico. The reason for her influence is that she is the daughter of Mr. J. Edgar Thomson, the chief engineer of the Pennsylvania, and the man who is to be my superior when I start work with the railroad.” John was scheduled to meet Edgar Thomson on Monday; he expected to discuss then his future duties and responsibilities at the line.

“She has influence just because she is his daughter?” Graham asked.

“No.” John smiled. “Kitty Lancaster has influence because she is his daughter, and she is a most unusual young woman. Or so I’m told.”

“I’m hungry,” said eight-year-old David Carlysle, interrupting.

“Don’t interrupt, David,” his father replied.

“That gives me very little room to maneuver,” Graham said with exaggerated, mock sadness. And the grin reappeared on his face.“It would seem so.”

At that moment, John, who had been looking down at his sons, raised his eyes to the platform and saw that Mrs. Lancaster was looking at him, as though she was aware she was being discussed, he thought.

“But I’m hungry David repeated.

“You’re always hungry,” Graham said.

John, meanwhile, nodded his head toward her, then dipped his hat. She gave a tiny nod in return, not sure whether she should know him or not.

“Is the ugly little man next to her Edgar Thomson?” Graham asked.

“Please, Father,” David said.

John sighed. “Alex,” he said to his twelve-year-old son, “would you take your brother to a food seller and find some-thing for him to eat.” He handed him a coin. “Here is twenty-five cents. That should do it.” Then he changed his mind and handed Alex a second coin. “Perhaps you could find enough for the rest of us. But stay away a long time,” he said, looking pointedly but fondly at his youngest son. “I’d like ten minutes of peace from David’s ceaseless cries of distress.” And then John returned his attention to Graham. “What were you saying, Graham?”

“Who is the man next to Mrs. Lancaster, the one she is talking to with such fervor?”

“He is the builder of this engine: Matthias Baldwin.”

“Why is she there?”

“For the sake of the ceremony I suppose. Mrs. Lancaster will probably christen the Tiger by smashing a bottle of champagne across its…” He paused, searching for the right word. And then it came to him, “Prow. So she rates being present at the center of the stage.”

“Lucky for us that she is so near,” Graham said.

John Carlysle smiled. He couldn’t agree with Graham more.

In England, John Carlysle had been a railroad man. In fact, he was one of the finest construction engineers in Britain. He had been trained at the University College in London, where he was one of the first to take a degree in the new discipline of civil engineering, and he was a member of both the British Institution of Civil Engineers and the prestigious Society of Civil Engineers, which had been in existence since 1771. Carlysle’s most recent accomplishment was the new line from London to Bristol. He had been in charge of that line from its first surveys to the laying of the last tracks. And he had finished the job on time and under budget. Once completed, Carlysle had been offered the job of building a line from Dublin to Belfast. But he had refused, for John Carlysle knew that he had no future in England. He had reached the limits not of his talents, education, and abilities but of his birth. He was the son of a blacksmith; and before he was a railway man, he had started out in life as a blacksmith. He had studied and worked hard; he had learned upper-class manners, language, and social graces; and he had come far. But not far enough to satisfy his deepest longings.

From the first moment he worked on a railway, John Car-lysle dreamed of owning and operating his own railroad. And as the years passed his dream grew grander. He wanted a railroad empire like the one his master and mentor Sir Charles Elliot was manifesting in England. Sir Charles had built or acquired lines from London west to Bristol and Penzance and north to Leeds and York. And if his designs materialized, as John was certain they would, Sir Charles would soon own connections with Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool, and Glasgow.

But Sir Charles was an aristocrat. He was born into the right family, he had attended the right schools, he had fought in the right regiments, he was friends with the right people, and he had married the right woman. Sir Charles was brilliant, talented, and ambitious—and all the right doors easily opened to him.

John Carlysle was at least Sir Charles’s equal in intelligence, talent, and ambition. And yet he was only too aware that in England a dream such as Sir Charles’s was unrealistic for a blacksmith’s son. He could manage Sir Charles’s, or someone else’s, railroad empire; but he could never own one.

Yet in America little was impossible.

Two years earlier John’s wife, Julia, had died of cholera. Julia had been a superb wife and mother—as warm and caring as she was beautiful; and John had been very much in love with her. She adored her new home in England. It would have been as painful for her to leave it as to leave her own body. So John had laid aside his personal ambitions and worked hard for Sir Charles. But after her death, the country of his birth began to lose its hold on him. And he started to dream again.

The crisis for John came in the fall of the previous year, 1851. He had known Sir Charles’s daughter Diane since she was a child, and as she had grown up, their paths had crossed cons

tantly and naturally, for Sir Charles had liked John very much and had often invited him to his city and country homes.

John and Diane also liked each other very much, even though they stood very far apart in the rigid British class structure. And yet, soon after Julia’s death, Diane naturally and almost unconsciously fell into the role of the leading woman in John’s sons’ lives. She did not try to replace Julia or mother them, which she and John knew was impossible and out of the question. Rather, she became a kind of aunt to them; the boys adored her.

The increasing closeness of John Carlysle and Diane Elliot did not escape Sir Charles’s notice any more than it escaped John’s or Diane’s. While they were not ready to act on their growing fondness for one another, Sir Charles was. One rainy, drab, chill day in November, John received a card from Sir Charles asking him to appear the following evening at his club. There would be supper, the card added.

John had been troubled before he received Sir Charles’s card, and was in greater turmoil afterward. He had not yet decided what to do about Sir Charles’s offer regarding the Dublin-Belfast line. He didn’t know whether to take the position or make a break with his mentor and sail to America where he could start fresh—and empty pocketed. He hardly had more than enough cash to pay for his own and his boys’ passage.

There was the greater question of what to do about Diane. He knew Sir Charles well enough to understand that even though the older man was very fond of John, he would never approve of John marrying his daughter. And although he cared greatly for Diane, John was not sure that he did in fact want to marry her. Nor was he sure that she wanted to marry him. There were moments when he yearned for her as much as he had ever desired Julia. And there were other moments when he thought he would be better off making a fresh start on his own in America. Shouldn’t she, he often thought, live her own life in her own land with her own kind?

When John arrived at the club, he found Sir Charles in a private room sipping claret in front of a roaring fire. Sir Charles was a slight man, slender nearly to the point of gauntness. Except for a fringe of sandy-gray hair, he was completely bald; and with his hollow cheeks and deep-set gray-green eyes, his head appeared as cadaverous as the skull on a pirate’s flag. But Sir Charles’s personality was anything but corpselike. He was as charged with power and energy as one of his own locomotives driving full-out along his main line.

The Trainmasters

The Trainmasters